The Centennial of Pierce v. Society of Sisters

The landmark decision legitimates the past, opens windows to the future of school choice

Pierce v. Society of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary is a landmark court decision worthy of a centennial celebration by those engaged in the school choice movement. Announced by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 1, 1925, it guarantees parents the right to send their children to a private school. Yet a realistic appraisal must appreciate Pierce more as a precursor for what came later than for what the opinion itself declared. Though the decision uses a compelling phrase that rings across time—“the child is not the mere creature of the state”—the decision is best understood as consolidating existing practice at the time rather than setting a new agenda for American schools.

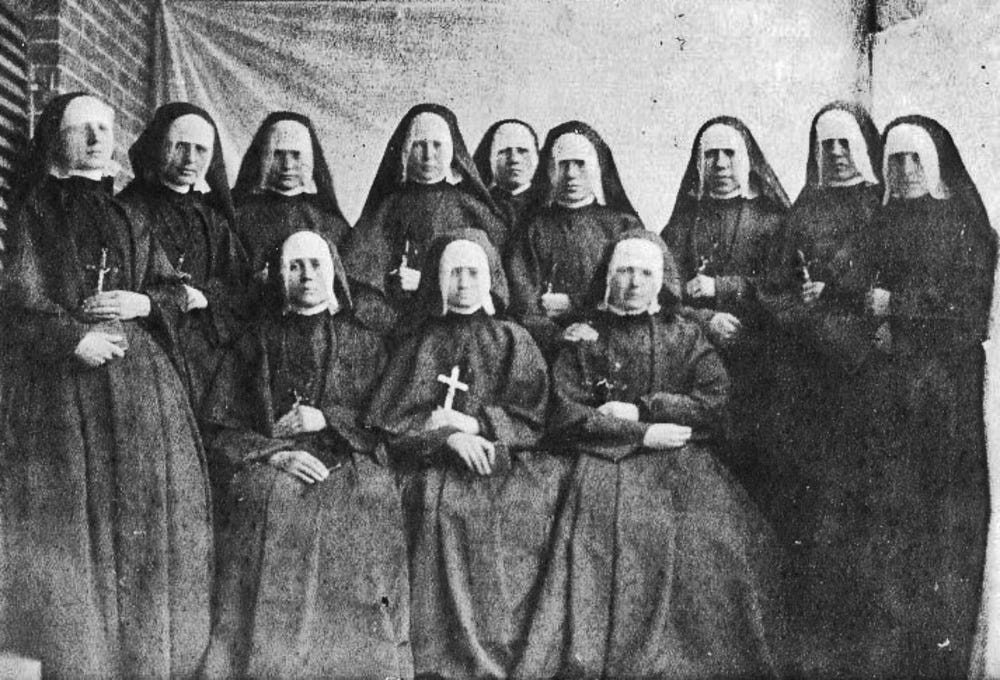

Source: Holy Names Heritage Center

In 1922, Oregon voters passed an initiative that would amend the state’s compulsory education law by deleting the private-school exception, thus compelling children between the ages of eight and 18 to attend public schools only. The Ku Klux Klan, known in the North as much for its anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic views as for its racist ideology, together with other like-minded organizations, campaigned successfully for the amendment. The law was about to take effect in 1926 when the Supreme Court, in Pierce, found it unconstitutional.

Pierce struck down an odious piece of legislation, and for that alone it deserves commemoration, but its practical effects were very limited. At the time, no other state or federal law prevented families from sending their children to private schools, though Nebraska had forbidden teaching in the German language, a restriction the Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional in Meyer v. Nebraska (1923).

The major issue facing private schools in the preceding decades had involved their financing, not their existence. Pierce does not address school finances in any way, nor does it give parents the right to withhold formal instruction at school. On the contrary, it says quite explicitly that “no question is raised concerning the power of the State . . . to require that all children of proper age attend some school.”

Today’s modern school-choice movement owes a debt to Pierce only because subsequent rulings took a direction the court did not foreshadow. Admittedly, the decision gives constitutional footing to alternative forms of schooling beyond the compulsory, state-directed school system established by the followers of Horace Mann. But Pierce neither questions bans on public aid to religious schools nor endorses homeschooling. Those innovations would arrive many court decisions later. Only then would today’s robust, tripartite system of school choice—private, charter, and homeschool—evolve to its current level.

To learn more about the history and impact of the Pierce decision, read my full feature article at Education Next.

Paul E. Peterson is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and the Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Government at Harvard University.